By Anthony Kaylin, courtesy of SBAM Approved Partner ASE

Implicit bias is a growing area of study and a recognized issue in the workplace. An interesting issue that has generated much research is whether certain words commonly used in job postings are discouraging candidates in protected groups, in particular women, from applying for certain jobs.

For example, recruiting for a coding specialist, some job postings have advertised for a “coding ninja,” i.e., a master coder. But the term “ninja” may be more attractive to males since it refers to master killers and violence as seen in movies and video games. “Rock star” could be another negative term; it may convey to job seekers that the workplace is full of loud egoists.

The institutionalizing of these words will also impact the culture of an organization and whether the organization is desirable to work at.

A 2011 study by Danielle Gaucher and Justin Friesen of the University of Waterloo and Aaron C. Kay of Duke University suggest that gendered wording (i.e., masculine- and feminine-themed words, such as those associated with gender stereotypes) may be an unacknowledged, institutional-level mechanism for maintaining inequality. In other words, job postings for jobs that are traditionally male dominated will likely use male suggestive words such as leader, competitive, and dominant.

Moreover, the study found that when job postings were constructed to include more masculine than feminine wording, participants perceived more men in those occupations and the postings were turn-offs for women applicants, who were less likely to apply for those jobs. Masculine-themed words were implicit cues that would dissuade women from applying because the words imply that women did not belong in the job. The study also found that male-dominated professions had job postings that had male-implying words.

The issue of belonging—i.e., using language that can indicate whether someone is welcome in a profession or not—is probably not one that recruiters and hiring managers consciously think of. For example, the public may perceive that there are more men within some occupations (e.g., engineering) than other occupations (e.g., nursing). The wording in many job postings often reinforces that perception. The study agreed with that hypothesis of belonging. Using different wording on job advertisements, the study found participants perceived more men within jobs that had masculine worded advertisements than jobs that had femininely worded advertisements, regardless of participant gender or whether that occupation was traditionally male- or female-dominated.

The real question is how this perception may play out in reality. The study posits that the diversity of the applicant pool will likely be highly influenced by how the ad is written. The study believes that women and men may equally like and want to work in an engineering job, but highly masculine wording used in postings reduces the appeal of the job to women because it cues that women do not belong. The study also posits that this subconscious yet implicit bias needs to be consciously identified to avoid potential discriminatory bias in job postings.

It should be noted that even if there are female applicants in traditionally male-dominated fields, although not discussed by the authors of the study, interview questions also need to be carefully constructed to not discourage applicants from persevering in the process or accepting offers if made.

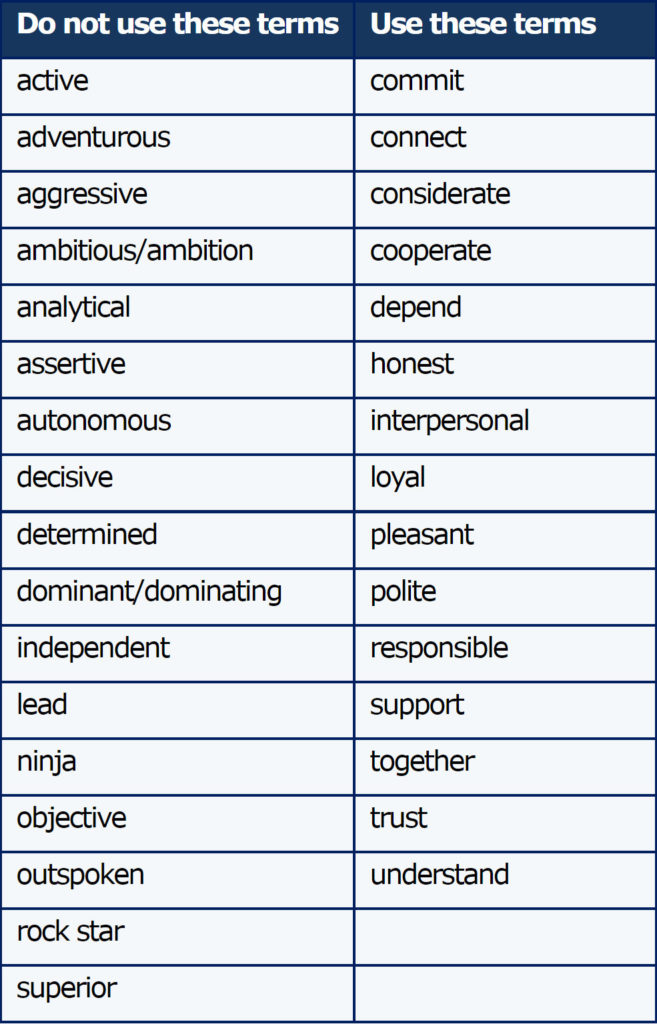

Recruiters, when composing job postings, should consider using/not using the terms in these lists:

By recognizing that there may be hidden or societal biases influencing language, recruiters can better attract a more diverse applicant pool by being more careful in word selection in both their job postings and their interview questions.

More recently, inside the workplace, Twitter engineers are changing normal IT nomenclature to be more inclusive. Regynald Augustin, a Black programmer at Twitter, made an effort to replace terms like “master,” “slave,” “whitelist,” and “blacklist” with words that didn’t hearken back to oppressive parts of United States history and culture. He recounted his thoughts at the time: “This has to stop. This isn’t cool. We have to change this now.”

But this issue is not new. In 2018, developers of Python programming language dropped “master/slave.” In 2014, Drupal online publishing software replaced the terms “master/slave” with “primary/replica.” In 2003, Los Angeles County asked suppliers and contractors to stop using “master” and “slave” on computer equipment.

But it is not just racial microinequities being addressed. Twitter is also reviewing other terms such as replacing “man hours” and “sanity check,” for example. Employees are becoming more conscience of the implications of words. Samples of changes made by Twitter include:

- Whitelist becomes allowlist

- Blacklist becomes denylist

- Master/slave becomes leader/follower, primary/replica, or primary/standby

- Grandfathered becomes legacy status

- Man hours becomes person hours or engineer hours

- Sanity check becomes quick check, confidence check, or coherence check

- Dummy value becomes placeholder value or sample value

“Inclusive language seeks to treat all people with respect, dignity, and impartiality,” said Twitter engineering chief Michael Montano in a June 25 email to all Twitter employees. “It is constructed to bring everyone into the group and exclude no one, and it is essential for creating an environment where everyone feels welcome.”

By being sensitive to words, it can derail subtle or unconscious acts of discrimination called microaggressions, argues Lecia Brooks, outreach director for the Southern Poverty Law Center, a civil rights group. “Words may mean nothing to the sender, but to the receiver it may mean something,” Brooks said. “If we can become more mindful about the words that we’re using, we can work to mitigate microaggressions,” she said.